If you exit Peckham Rye railway station in southeast London, you’ll be met with a flurry of activity.

Buses whip along the bustling Rye Lane, packed with people perusing stores to the faint pulse of Afrobeat rhythms. At every turn, brick walls are painted with bold strokes of street art, their vibrancy competing with grocery storefronts laden with fruits and vegetables and stacked crates of plantain. For decades, the multicultural community of Peckham has been a destination for Nigerians moving abroad – so much so that it’s earned the nickname “Little Lagos.”

“There’s a spirit here,” said filmmaker Adeyemi Michael who was born in Lagos and raised in Peckham. When he was growing up, Michael skated up Peckham Rye to buy groceries for his mom, and says he felt embraced by the Nigerian community there. “The high street reflect(ed) my experience growing up as a Nigerian-born South Londoner,” he recalled.

“I’ve been moving around a lot these days,” Michael added. “Whenever I come back, I’m always met by the soul of this area and the people who still remain here, most of (whom) are immigrants and people who come from different walks of life.” Now, this corner of London’s relationship with the Nigerian diaspora is being explored in a new exhibition, “Lagos, Peckham, Repeat: Pilgrimage to the Lakes.”

Lagos, Peckham, Repeat

Held at South London Gallery, the exhibition features sculpture, installation, photography and film. Step inside and you’ll be greeted by the distant bustling street sounds of Nigeria’s largest city. From cars blaring their horns to bus conductors calling out their routes, the ambient soundscape is the work of Emeka Ogboh, one of 13 Nigerian and British Nigerian artists featured in the exhibition.

The exhibition is co-curated by Folakunle Oshun, an artist who founded the Lagos Biennial, a non-profit platform supporting contemporary art in the city.

Oshun spent most of his childhood in Nigeria, but for much of the past decade he has lived and worked in Berlin and Paris. Over the last eight months, however, he has immersed himself in Peckham and its British Nigerian community, to see how Little Lagos has built up its identity since Nigeria’s independence from Britain in 1960.

“You have to go to the very beginning of how Nigerians made Peckham home,” Oshun told CNN.

“All over the world you have migration, there are always pockets where people cluster because of their shared values, tradition, and in this context, I’d say there’s also an economic element to it.”

For Oshun, there is huge pride telling the story of the Nigerian diaspora: “For way too long the migrant communities in the UK have always taken a back seat. For this show it was really important to give the artists that voice and create a show that’s super empowering for years to come.” Margot Heller, South London Gallery’s director, said the exhibition uses Lagos as an entry point to look at wider issues around migration, shifting senses of identity and the idea of home.

She explained that over the last few decades there has been significant growth in Peckham’s Nigerian community, coming in waves throughout the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, with people purchasing property and setting up businesses.

“Peckham became known as a kind of second home for people visiting the UK from Nigeria,” she said. “Some of them staying, and some of them returning, which is very much part of the exhibition concept.”

‘It’s a statement’

One Nigerian who stayed is Michael’s mother. She is the star of his short film “Entitled,” which is featured in the exhibition.

Dressed in a gele head tie and traditional clothing, she is filmed proudly mounted on a horse riding through the streets of Peckham Rye on an early morning. Initially, “Entitled” was born out of frustration, Michael explained. He felt his mother was being side-lined in a job she worked for 25 years, because she was a first-generation Nigerian immigrant.

He began looking at Napoleonic images of people considered conquerors, and researched Frederich Lugard who furthered British imperialism across West and East Africa. Michael wanted to portray his mother as having the same kind of power, in the clothing of her Yoruba heritage (one of Nigeria’s three largest ethnic groups).

“When you see my mum dressed in traditional Yoruba wear on a horse in Peckham, it’s a statement,” he said. “I did that for her, for other people too – it means something.”

Just as Michael’s work is deeply personal, he said the other pieces in the exhibition are equally meaningful to their creators. Artist Temitayo Ogunbiyi’s play sculpture, designed for visitors to interact with, was inspired by the flight route from Lagos to London, as well as plants she has encountered in the Nigerian city.

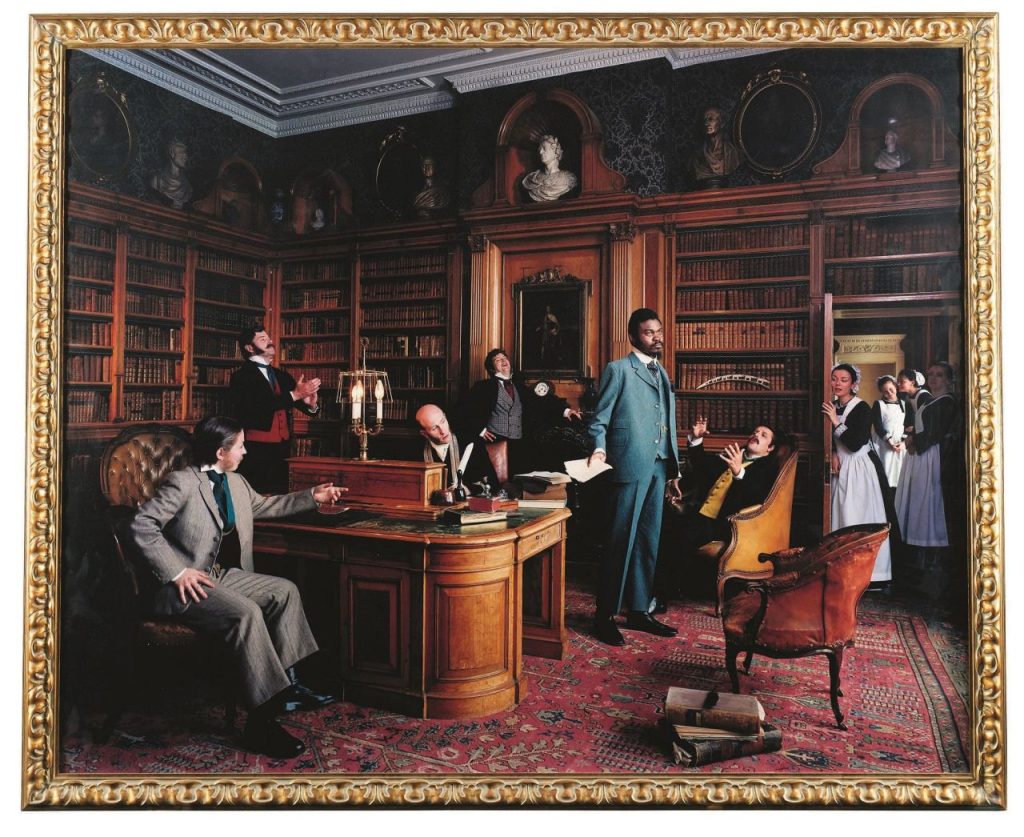

Turner Prize nominee Yinka Shonibare appears in his work “Diary of a Victorian Dandy” (1998) which partly reflects on his own life as a Black man living with a physical disability.

“They’re quite personal, specifically about Nigerian culture, the artist’s relation to Nigeria, and what it means to be Nigerian,” Michael said.

“Peckham was never the area people wanted to come to, but you see it now and it’s incredible,” he added. “People are unashamedly who they are.”

“Lagos, Peckham, Repeat: Pilgrimage to the Lakes” is running until October 29, 2023 at South London Gallery.

— CutC by cnn.com