Children as young as nine have been added to malicious WhatsApp groups promoting self-harm, sexual violence and racism, a BBC investigation has found.

Thousands of parents with children at schools across Tyneside have been sent a warning issued by Northumbria Police. One parent, who we are calling Mandy to protect her child's identity, said her 12-year-old daughter had viewed sexual images, racism and swearing that “no child should be seeing”.

WhatsApp owner Meta said all users had “options to control who can add them to groups”, and the ability to block and report unknown numbers. Schools said pupils in Years 5 and 6 were being added to the groups, and one head discovered 40 children in one year group were involved.

The BBC has seen screenshots from one chat which included images of mutilated bodies. Mandy said it took some coaxing, but eventually her daughter showed her some of the messages in one group, which she found had 900 members.

“I immediately removed her from the group but the damage may already have been done,” she said.

“I felt sick to my stomach – I find it absolutely terrifying.

“She's only 12, and now I'm worried about her using her phone.” Northumbria Police said it was investigating a “report of malicious communications” involving inappropriate content aimed at young people.

“We would encourage people to take an interest in their children’s use of social media and report any concerns to police,” a spokesperson said.

‘Playing on their mind'

The WhatsApp messaging app has more than two billion users worldwide. It recently reduced its minimum age in the UK and Europe from 16 to 13, while the NSPCC said children under 16 should not be using it.

The charity said experiences like Mandy's daughter's were not unusual. Senior officer for children's safety online, Rani Govender, said content promoting suicide or self-harm could be devastating and exacerbate existing mental health issues.

“It can impact their sleep, their anxiety, it can make them just not feel like themselves and really play on their mind afterwards,” she added. Groups promoting harmful content on social media have featured in high-profile cases, including the death of Molly Russell in 2017.

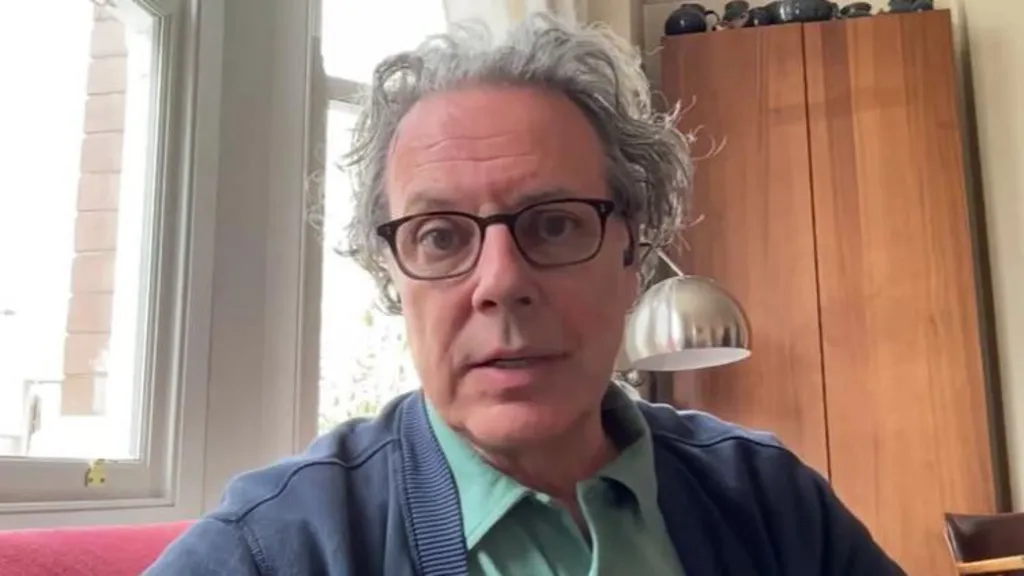

An inquest concluded the 14-year-old ended her life while suffering from depression, with the “negative effects of online content” a contributing factor. Her father, Ian Russell, said it was “really disturbing” there was a WhatsApp group targeting such young children.

He added the platform's end-to-end encryption made the situation more difficult.

“The social media platforms themselves don’t know the kinds of messages they’re conveying and that makes it different from most social media harm,” he said.

“If the platforms don’t know and the rest of the world don’t know, how are we going to make it safe?”

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak told the BBC that, as a father of two children, he believed it was “imperative that we keep them safe online”. He said the Online Safety Act was “one of the first anywhere in the world” and would be a step towards that goal.

“What it does is give the regulator really tough new powers to make sure that the big social media companies are protecting our children from this type of material,” he said.

“They shouldn’t be seeing it, particularly things like self-harm, and if they don’t comply with the guidelines that the regulator puts down there will be in for very significant fines, because like any parent we want our kids to be growing up safely, out playing in fields or online.”

Mr Russell said he had doubts about whether the Online Safety Act will give the regulator enough powers to intervene to protect children on messaging apps. It was “particularly concerning that even if children leave the group, they can continue to be contacted by other members of the group, prolonging the potential danger”, he said.

He urged parents to talk to even very young children about how to spot danger and to tell a trusted adult if they see something disturbing. Mandy said her daughter been contacted online by a stranger even after deleting the chat.

“She also told me a boy had called her – as a result of getting her number from the group – and had invited ‘his cousin’ to talk to her too,” she said.

“Thankfully she was savvy enough to end the call and reply to their text messages saying she was not prepared to give them her surname or tell them where she went to school. ”

‘Profits after safety'

Mr Russell said parents should never underestimate what even young children are capable of sharing online.

“When we first saw the harmful content that Molly had been exposed to before her death we were horrified,” he added. He said he did not think global platforms would either carry such content or allow their algorithms to recommend it.

“We thought the platforms would take that content down, but they just wrote back to us that it didn’t infringe their community guidelines and therefore the content would be left up,” he said.

“It’s well over six years since Molly died and too little has changed.

“The corporate culture at these platforms has to change; profits must come after safety.”