As accidental adverts for art shows go, a giant pooch made of flowers is a crowd pleaser. Outside the Guggenheim Bilbao in northern Spain, Jeff Koons’ much-loved flower 1992 sculpture “Puppy,” shows how Pop art — that high kick of counter-intuitive artistic expression so often equated with the 1960s — never really went away.

It’s appropriate then, that Koons’ monumental 43ft-high Highland Terrier made of 38,000 bedding plants sits faithfully — and spectacularly — outside the museum’s new show “Signs and Objects: Pop Art from the Guggenheim Collection.”

The exhibition both celebrates and deconstructs Pop – the artistic movement that reframed everything from comics to product packaging as high art in a mashup of Dada, Surrealism and, some would say, chicanery. The show delivers bombastic examples by many of the old masters — Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg — while pondering whether Pop has a place in today’s cultural landscape.

Curators present Warhol’s silkscreened electric chairs — “When you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn’t really have any effect,” he once remarked — and Lichtenstein’s cartoonish studies using Ben Day dots. But there are also whimsical works from the 1990s and 2000s by Claes Oldenburg and Maurizio Cattelan (who presents a bitterly comic sculpture of Pinocchio drowned in a pond), and more recent politically minded pieces by contemporary artists such as Lucia Hierro, whose work addresses cultural identity as much as the effects of capitalism and consumerism. The Pop baton has been handed over numerous times in art history.

The Guggenheim Museum was pivotal to the development of the movement, both in terms of its fame and its art historical importance. In 1963 it staged the New York exhibition “Six Painters and the Object” in which works by Warhol, Lichtenstein and Rauschenberg joined those of Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist and Jim Dine in their museum debut, solidifying the artists’ scholarly importance. And the museum has been collecting in the field ever since.

The Bilbao show includes 40 works, dating from 1961 to 2021. The largest,“Soft Shuttlecock” (1995) by Claes Oldenburg and his wife Coosje van Bruggen, was specifically created for the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan. In Bilbao, the monstrous shuttlecock with its flaccid feathers sits in its own space like a sad echo of an ancient badminton game between giants. Pop can be funny and melancholy at the same time.

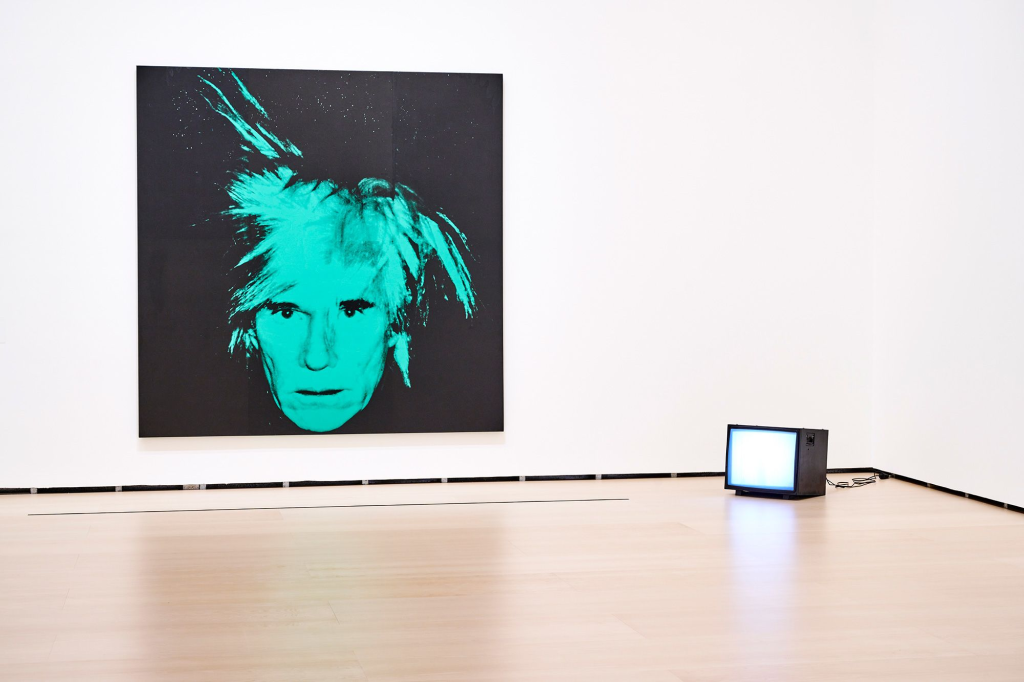

The show is primarily spread over two main galleries, the first showing large-format high-sheen works by, primarily American A-listers — including a huge green self portrait of Warhol looking like the Wicked Witch of the West — while the second shifts the focus to European artists, such as Mimmo Rotella and Sigmar Polke). Audiences move from the “new, shiny” realm of a young country to the regions with “long histories”, notes Lauren Hinkson, who has co-curated the Bilbao exhibition with fellow Guggenheim scholar Joan Young.

Pop has become synonymous with the stuff of shop shelves and self-promotion. So, is it partly responsible for today’s rabid consumerism and narcissism? “Sure,” says Hinkson. “Andy Warhol chief among them. He did it before anyone had thought to do it, before the Kardashians even thought to take a selfie. Warhol anticipated all of that.” Those original Pop pioneers, she notes, “turned a mirror back on the culture, they made the public self-aware.” And today, she adds, contemporary artists are injecting wit into the mix. “But it’s an incredibly dark read.” Poor old Pinocchio is a case in point.

In the exhibition entrance, “A Little Bit of Everything (2017-21)” by the Dominican American contemporary artist Lucía Hierro, highlights the potential of Pop to be both critical and culturally specific. Hierro has created a giant shopping bag full of Latin-American groceries that briefly baffles audience’s sense of scale. The work, created in collaboration with her late mother Lucía Guzmán García, features a selection of oversized felt replicas of Dominican products, all jumbled together. It’s a strange melding of the personal, political and whimsical.

Talking from her studio in New York, Hierro explains how she brings an outsider’s perspective on the movement, blending politics – in particular discussions of colonialism – and family lore into an aesthetic often thought of as universal and generic. “I see myself in an interesting position as a Dominican American and Spanish-speaking Caribbean to confront and analyze my place within these systems, within the visual analysis we call ‘Pop’.”

Like many of the works on view in ‘Signs and Objects’, Hierro’s work is as playful as it is profound. “I’ve always loved humor in art,” says Hierro. “Humor is a great way to engage with each other, especially when wanting to broach heavier subjects. It’s not passive like entertainment; it’s collaborative.” Outside the museum, Koons’ giant hound of marigolds and begonias punctuates her point perfectly. As people pass, they giggle and get their Instagram snaps. Pop was never going to get just 15 minutes of fame.

— CutC by cnn.com