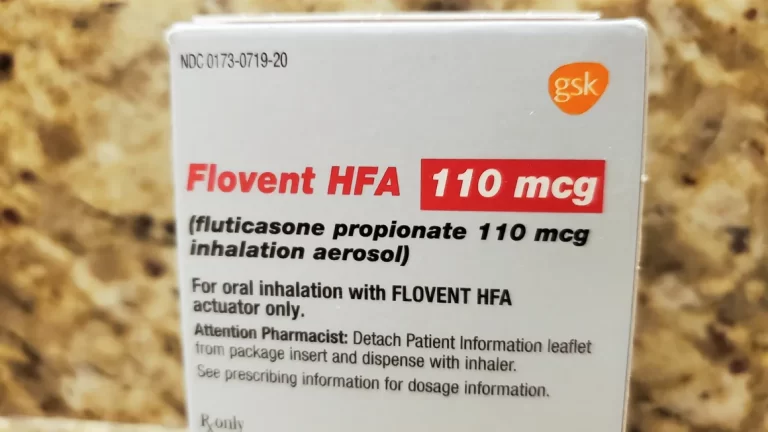

Flovent, one of the most commonly prescribed childhood asthma medications, is no longer being manufactured in the United States. GSK, the pharmaceutical company that made it, took if off the shelves January 1 and replaced it with an identical generic version, fluticasone.

But what seemed to be a straightforward swap has left some doctors, nurses and parents of children with asthma scrambling for medications to care for young patients.

Flovent and its generic belong to a class of asthma medications known as controllers. They work by reducing inflammation in the airways of children with asthma that puts them at risk of flaring — having an asthma attack — when exposed to a trigger.

For children with severe asthma, the medication is both necessary and lifesaving.

Four-year-old Bryce Cohen is one of those children. He was only 8 months old when he was first in the pediatric ICU for trouble breathing. He was hospitalized again two months after that. In the years since, he has been able to stay out of the hospital, due in large part to Flovent. His asthma has flared up only one time: last summer, when his family and doctors attempted to give him a break from the daily inhaler and he caught a cold.

Bryce lives in New York City and is a patient at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. His family hasn’t been able to get the new generic version of Flovent in the past month.

“This is a really big issue, and it’s scary to think that we are in the middle of cold season,” said Rebecca Baye Cohen, Bryce’s mom. She said she has been calling friends and relatives for weeks in search of extra Flovent inhalers.

Some physicians across the country are also reporting that they can’t get their patients’ asthma medications. The reason: Their insurance does not cover the generic that GSK introduced after Flovent was taken off the shelves and alternative medications may not work or can be hard to find.

CNN reported in December that physicians were raising alarm about the coming change to prescriptions and coverage. At the time, a spokeswoman for GSK said the company was shifting from Flovent to fluticasone “as part of our commitment to be ambitious for patients,” adding that the generic would “provide patients in the US with potentially lower cost alternatives of these medically important products.”

Experts who follow the industry pointed out that the switch happened at precisely the time a provision in the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act went into effect. In it, a change in Medicaid rebates would have caused GSK to have to pay large penalties after increasing the price of Flovent at a rate higher than inflation for years. The penalties could have incurred rebates to Medicaid greater than the price of the drug, meaning GSK would have had to sell Flovent to Medicaid at a loss.

The authorized generic, fluticasone, would be the same product, but without the branding and history of price increases that would leave the medicine vulnerable to large rebates to Medicaid.

“Obviously, Pharma doesn’t want to be selling at a loss on anything in its portfolio,” Andrew Baum, an analyst who covers the stock of GSK and other pharmaceutical companies for the financial firm Citi, said in December. “So it seeks to evade impact by, one: discontinuation; two: authorized generic.”

Substituting one medication with the other “seems like it should be great,” said Dr. Stephanie Lovinsky-Desir, chief of the Division of Pulmonology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “The problem is that insurance companies have not listed fluticasone as the preferred medication on their formularies.”

Lovinsky-Desir and I are colleagues from different departments at Columbia. For this story, I also spoke with other pediatricians across the country who reported similar struggles in getting patients the care they need.

Insurance formularies are a list of prescription drugs that are covered by specific insurance plans, and the lists are based on how appropriate the medication is for a given condition, as well as on cost. If a medication is not on the formulary, providers must submit a prior authorization — a request for approval to get the medication covered without the patient having to pay out of pocket.

“It’s all a big game,” says Victoria Piane, a pediatric nurse practitioner at Columbia University Irving Medical Center who said her team has been receiving 10 to 15 requests per day for prior authorizations from local pharmacies for the Flovent generic and age-appropriate medications not listed as preferred.

“It’s not just ‘send a simple prescription’ anymore,” she added, explaining that she spends an average of an hour on the phone per request, sometimes without resolution.

In addition to the volume of paperwork, when it comes to children with asthma, the process is flawed, Lovinsky-Desir said. Some of the alternatives covered on formularies are not clinically appropriate for small children, she said.

Although Flovent and its generic are easy to deliver in a minute or two, commonly listed alternatives such as dry powder inhalers or breath-actuated pumps require children to take deep breaths and hold their breath for at least 10 seconds, a maneuver young children are not able to do. Nebulizer treatments are another alternative, but those require 10 to 15 minutes twice a day for a young child to sit still, Lovinsky-Desir said.

And in some cases, insurance companies require patients to show that they have tried preferred medications and failed before they can grant approval for one that’s not listed.

Four-year-old Ana, also a patient at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, has been to the intensive care unit twice, both times requiring continuous positive airway pressure, or CPAP, to breathe. On Flovent, she finally stabilized and stayed out of the hospital, said her mother, Mariluz.

“So you’re telling me, as a mother who has had her daughter in the ICU twice on a CPAP machine, that she should try and fail something?” said Mariluz, who did not want to use their last name to protect her daughter’s privacy. “Does trying and failing mean we have to go to the ICU again?”

Why wouldn’t insurance companies add fluticasone to the formularies?

In an emailed statement, Optum Rx, the pharmacy care services business of UnitedHealth Group, said GSK introduced the generic version of Flovent at a “much higher net price” than the prior price of the name-brand drug.

Optum Rx has instead added QVAR and Arnuity, both breath-actuated pumps, to its formulary. The net cost to plan sponsors is 70% to 80% less than the newly launched fluticasone alternative, Optum Rx said. It also described the move by GSK as one that “puts profits before patients.”

In response, a spokeswoman for GSK said the company made “a business decision” to launch the generic version of Flovent “as a way to ensure patients continue to have access to these important medicines, potentially at a lower cost, knowing that we had been planning to discontinue the branded products for some time.”

GSK said it partnered with Prasco LLC to manufacture and distribute the generic version of Flovent “and Prasco alone determines the market price for those authorized generics.” GSK proactively notified payers and pharmacy benefit managers, also known as PBMs, of the change beforehand, the spokeswoman noted.

But with Flovent now off the market, some doctors say they are struggling to get the generic or other alternatives for their patients. The change is happening as the United States is still experiencing high levels of respiratory viruses including flu, RSV and Covid-19.

“The discontinuation of Flovent has been an unmitigated disaster,” said Dr. Christopher Oermann, a pediatric pulmonologist and director of the Division of Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonary at Children’s Mercy Kansas City.

With Flovent gone, some payers have added the medication Asmanex to formularies. It’s an inhaled corticosteroid also aimed at decreasing airway inflammation and is delivered via a metered-dose inhaler, in the same way Flovent is. Within a few days, it was hard to find, Oermann noted, and it’s now in short supply around the country.

In Boston, Dr. Ben Nelson, a pediatric pulmonologist at Mass General for Children, said that even when his team is able to identify an alternative and file the appropriate paperwork, the medications are labeled as “tier 3 drugs” by insurance formularies, which require a higher copay.

“Many families cannot afford the 150 dollars per month (or more) for their child’s life saving medication,” Nelson wrote in an email. Dr. Christy Sadreameli, a pediatric pulmonologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Maryland, said “many kids” are falling through the gaps.

“This is the worst I have ever seen in my career with respect to difficulty getting the right drug in the right type of inhaler to the right age patient,” she said. Lovinsky-Desir said she and her team are doing everything they can to keep children out of the hospital but have had to send several young patients to the ER when their symptoms could not be controlled.

The only medication Ana has been able to get is a budesonide nebulizer, Mariluz said. The noise of the machine reminds Ana of her time in the ICU, which inevitably makes her cry. Mariluz puts a pillow over the machine every morning and night to hide the reminder.

Bryce has also been unable to get authorization for the Flovent generic from his parents’ insurance. Instead, he got authorization for Asmanex, which his family couldn’t find in New York. He is OK for now; an aunt who lives in Arizona was able to get an inhaler there and shipped it to New York.

— CutC by cnn.com