Lee Hee Tae had high hopes for his sex festival, which he proudly billed as South Korea's “first and largest”.

He envisaged 5,000 fans flocking to see their favourite Japanese porn actors and actresses, who were being flown in for last weekend's event. There was to be a bondage fashion show, a sex toy exhibition, and some adult games, that involved bursting balloons between people's bodies.

But with just 24 hours to go, the festival was cancelled. South Korea is known for its conservative approach to sex and adult entertainment. Public nudity and strip shows are banned, and it is illegal to sell or distribute hard-core pornography, though not to consume it.

“Virtually every developed country has a sex festival, but here in South Korea we don't even have an adult entertainment culture. I want to take the first steps towards creating one,” said Lee Hee Tae, whose company Play Joker produced legal soft-core pornography before their pivot to organising events.

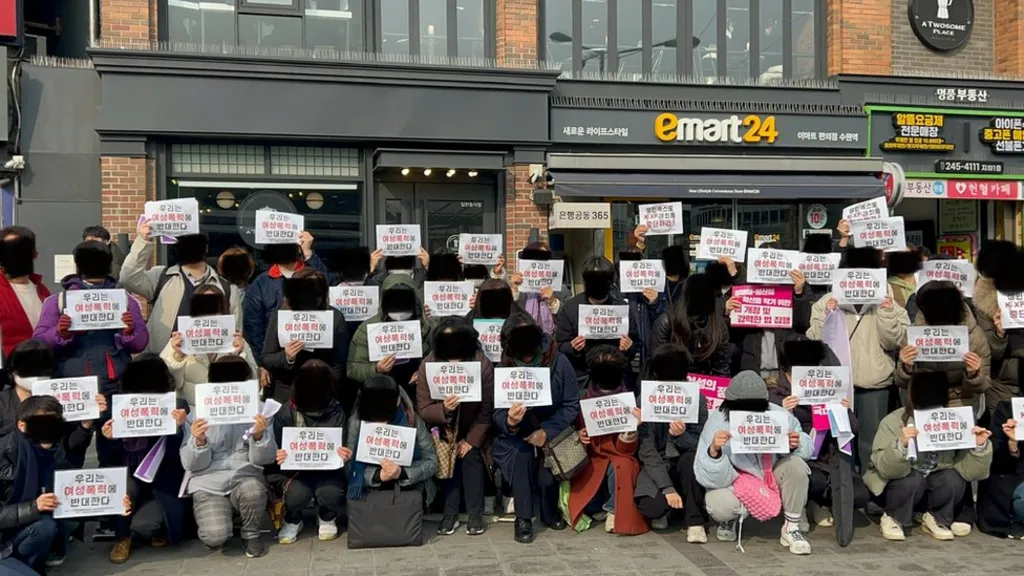

A month before, women's rights groups from the town of Suwon, where the event was due to be held, came out to protest. They accused the festival of exploiting women in a country where gender violence is endemic.

This was not, they argued, a festival aimed at both sexes. The heavily female, scantily-clad advertising suggested ticket holders were likely to be overwhelmingly male. The local mayor condemned the event for taking place near a primary school and the authorities threatened to revoke the venue's licence if it went ahead. The venue pulled out.

Frustrated, but unfazed, Mr Lee switched locations, but a similar chain of events played out. The new authority accused the festival of “instilling a distorted view of sex” and insisted the venue cancel. Next, Mr Lee found a ship docked on the river in Seoul. But, following pressure from the council, the boat's leaseholder threatened to barricade it and cut off the electricity if its promoter allowed the festival to go ahead.

At each turn, Mr Lee had to scale down the festival as ticket holders called in refunds, costing him hundreds of thousands of pounds. Nearly out of options, he found a small underground bar in the glitzy Gangnam neighbourhood in Seoul, that could hold around 400 people. This time he kept the location a secret.

So, Gangnam council wrote to every one of its hundreds of restaurants warning them they would be shut down if they hosted the festival, accusing it of being “morally harmful”. But the bar stood its ground.

Then, the day before, the Japanese porn stars pulled out. Their agency said the backlash to the festival had “reached fever pitch” and the women were worried they might be attacked and even stabbed.

From his office in Gangnam, Mr Lee told the BBC he was shocked events had taken “such an unthinkable turn”, adding that he had received death threats. “I have been treated like a criminal without doing anything illegal”, he said, stating that the festival fell well within the lines of the law. There was to be no nudity or sexual acts performed, similar to an event he held last year, which garnered little publicity.

Play Joker has staged attention-grabbing stunts in the past. Last year they had a woman parade the streets of Seoul wearing nothing but a cardboard box, inviting passers-by to put their hands inside and touch her breasts.

Mr Lee says he wants to challenge Korea's attitudes to sex and pornography, which are stuck in the past.

“The authorities are hypocrites. If you go online everyone is sharing pornography, then people log off and pretend they are innocent. How much longer are we going to keep up this pretence?”

Although popular international porn websites cannot be accessed from South Korea, most know how to use internet VPNs to override restrictions.

The group that protested the original event, the Suwon's Women's Hotline, described the festival's cancellation as a “triumph”. “Whatever the organisers say, this was not a celebration of sex, but the exploitation and objectification of women, and the sex industry encourages violence against women,” said Go Eun-chae, the director of the hotline that provides support for victims of domestic violence.

Ms Go and other women's rights organisations in Korea argue the country has a problem with sexual violence that needs urgent attention. “It pervades our culture,” she said, adding that men had endless opportunities to freely express their sexuality without needing a festival to do so.

Bae Jeong-weon, who lectures in sexuality and culture at Sejong University, said one of the issues with the festival was that it was mostly geared towards a male audience.

“There is a lot of violence against women here, and so women are much more sensitive to issues of exploitation,” she said. In a 2022 survey by the government's gender ministry, more than a third of women said they had experienced sexual aggression.

“In South Korea we have a history of talking about sex negatively, in terms of violence and exploitation, rather than as a positive, enjoyable act,” Ms Bae added.

In Gangnam, where the festival was eventually due to take place, the neighbourhood's mostly younger residents appeared divided according to their gender. “It's not pornographic and they're not doing anything illegal, so I don't think it should have been blocked,” said a male IT worker Moon Jang-won. But 35-year-old Lee Ji-yeong said she sympathised with the various councils and was “repulsed at the festival for commercialising sex”.

But most agreed that by banning the festival, the authorities had overreached.

“This ban was a decision by old, conservative politicians who want to appeal to older voters,” said 34-year-old Yoo Ju. “This generation still believes that sex must be hidden,” she continued, adding that young people's attitudes to sex were shifting, and that she and her friends talked openly about it.

Politics in South Korea is still largely guided by conservative, traditional values and authorities have been accused of overreaching before, stifling diversity. Last year, Seoul city council stopped Queer Pride being held on the city's main plaza following opposition from Christian groups. The government has yet to pass an anti-discrimination law which would protect both the queer community and women, both of whom face significant prejudice.

The controversy over the sex festival has seen these two issues of sexual diversity and gender equality become entangled, with the organisers arguing authorities were stopping people from freely expressing themselves, and women asserting that their rights were being violated.

The authorities will have to figure out how to navigate this tricky dilemma. Play Joker told the BBC it plans to try again to host the festival in June, only bigger, with Mr Lee claiming to now have several politicians on his side. Over the weekend, the mayor of Seoul issued a statement on his YouTube channel stating the city had “no intention of getting involved in the future”.