In a class of 30 children, no two learn the same way and a teacher does not have time to instruct them all differently. But artificial intelligence does – and across the East of England it is being used to modernise and personalise education. The aim is to ensure no child gets left behind and that learning is engaging, but how can teachers ensure the technology is not abused?

In a hangar at West Suffolk College in Bury St Edmunds lies an XR Virtual Reality Lab.

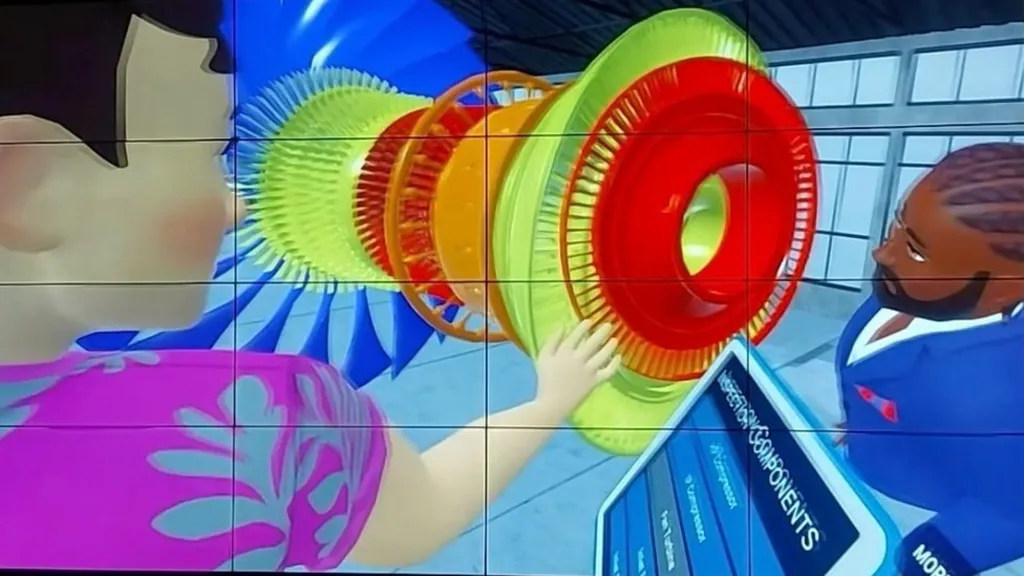

This £2m futuristic-looking pod, built using government funding, uses AI to create virtual 3D worlds that students can access through headsets or tablets, immersing them in their subjects. It also “gamifies” the curriculum to engage students.

It is the pride and joy of Nikos Savvas, the chief executive of the Eastern Education Group which operates several colleges in the region. He says: “We teach in an antiquated way which only works for the minority. We need to move out of the Victorian ages. Why can't learning be fun?”

Mr Savvas believes most people learn best through experience.

“We tested this with primary school children. They were taught traditionally about ancient Egypt and then asked to write about it.

“Next, they were given a headset which allowed them to walk through the pyramids in a virtual world. You should have heard their shrieks of joy.

“When they wrote about Egypt for a second time, the difference was incredible.” The technology is used for many courses. For example, engineering students can meet in a virtual room and work together to build a plane engine.

Tom Lloyd, who runs the lab, says “it gives them confidence and experience before working with real parts, which are expensive and can be difficult to access”. But is there a danger that students, who already live in a screen-reliant society, will be over-stimulated by yet more gamification? Mr Savvas believes that done properly, the answer is ‘no'.

“We ensure there is a balance between classroom, outdoor and virtual learning. That protects mental health,” he says. Few places in the country have facilities like this and Mr Savvas hopes the trials he is running allows others to follow.

But AI does not have to be this costly to bring benefits. The Bedford College Group uses AI across its sites in Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire to help GCSE Maths and English students.

On computers they work through a series of modules set by the teacher. The AI analyses how they answer questions, flagging up areas they struggle with and personalising the learning by giving them more practice.

Sara Pryce says teachers, like her, are still “central to the process but students don't have to wait for me to mark their work, they know instantly if they're on track and they can work at their own pace”. For English teacher Richard Rochester it provides an “invaluable and instant understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of new students”, so no time is lost.

Student Alexandra Balogh, 18, says: “I love it. At the beginning my grammar was really bad, but now I have confidence in class and in my assignments. It's made me realise what I'm capable of.”

Mahidur Chowdhury, 18, also praises the programme. “I'm using it to practise compound interest. It's good because you can keep trying it until it gets into your head,” he says. The AI programme is used mainly for homework and the vice principal, Nina Sharp, says it is delivering results.

“Grades for students who'd used Century Tech were 5% higher for maths and 10% higher for English,” she says.

Increasingly, staff also use AI to produce lesson plans. Ben Lewis, course director for e-sports at West Suffolk College, says most teachers plan lessons in their own time.

“It can take hours and adds to an already heavy workload. AI programmes can plan a lesson in minutes,” he says.

“We have to check it and tweak it, but that takes far less time than planning from scratch.” But teachers understand this technology can be abused. Some students ask AI to write entire essays for them.

“Students must be taught to use AI responsibly,” Mr Lewis says. “I say to them, ‘Use it, like you'd use me.' ‘Ask it questions for research, but don't expect it to do the work for you.'”

The college is setting up an AI Board, which will review the work of anyone thought to have taken unreasonable advantage of the technology.

Students will have to present their knowledge of the subject to staff to ensure they understand it. Across the region, teachers feel this process will become more common. Teachers accept that artificial intelligence is here to stay. The challenge is how to harness its potential while avoiding the pitfalls.

The Department for Education is still investigating how AI will change learning and teaching in order to develop a future policy. Education Secretary Gillian Keegan said: “It's crucial we get our approach to it right.

“It's heartening that many education professionals are already seeing the tangible benefits of AI while remaining alert to its risks.”