It had been that long they had worked out the exact number of days – 4,095.

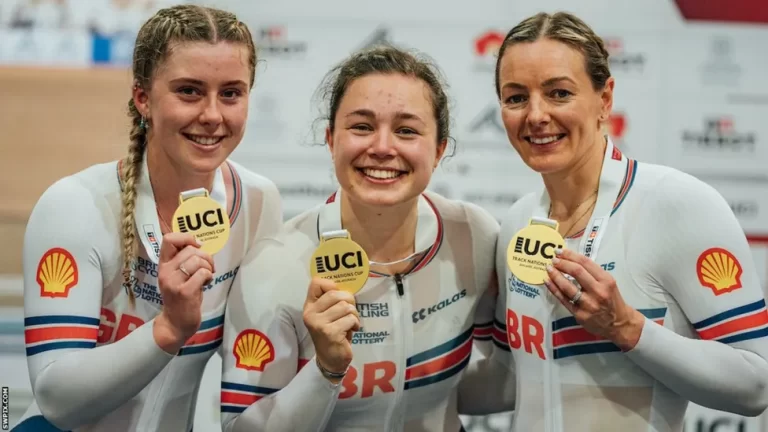

Not since late 2012, more than 11 years earlier, had a British women's team sprint squad won a gold medal. But at the Adelaide leg of the Track Nations Cup in February, Katy Marchant, Emma Finucane and Sophie Capewell finally bucked that trend.

Such had been Great Britain's lack of success, they did not even qualify for the team sprint at the Rio or Tokyo Olympics, while individual medals started to dry up after 2016. By 2019, the squad had had enough and made a pact – they wanted to “change the narrative”., external

“We realised we weren't going to qualify for Tokyo in the team sprint. We decided we didn't want this to happen again,” says Capewell.

“We didn't want to be the squad that was having to find different avenues to qualify for an Olympics. We wanted to be a force.” That is what they are now. Five years on, GB's women are enjoying success across all the sprinting disciplines, and with the Paris Olympics just around the corner, their story tells a different tale.

The ‘weakest link'

Sprinting success was not sparse in the heady days of London 2012. Victoria Pendleton won two medals, including keirin gold, and it would have been three had she and Jess Varnish not been disqualified from the team sprint final.

The following year, Becky James won two golds and two bronzes at the World Championships, and would also go on to win world bronze in the keirin and team sprint with Varnish in 2014, and the same colour in the keirin in 2016.

At the Rio Olympics, James won double silver while Marchant won individual sprint bronze.

Then came the drought. From 2017 to 2020, Britain's female sprinters won no medals at World Championship level, and only one – a team sprint silver in 2020 – at the Europeans.

At the postponed Tokyo Olympics in 2021, having not qualified in the team sprint for the second successive Games, Marchant was the sole female sprinter in the Team GB squad and came home empty-handed. With British Cycling's sustained success across all disciplines continuing around them, Finucane said the squad felt they were classed as the “weakest link”.

“We felt like the tag-along squad at one point. Our seat at the table didn't feel as powerful as everyone else's,” adds 25-year-old Capewell. “We wanted to be on that table of success.”

“You want to be the talk of the town, and I've been the talk of the town for the wrong reasons when you're not getting the medals,” says Marchant, 31.

“It's really nice now to be a part of something that is getting the results and is getting recognised, and now all of a sudden everyone's talking about the women's sprint.”

What has changed?

Marchant says it was in the lead-up to Tokyo that she noticed a shift, with work being done by British Cycling at the foundation level to build the numbers of female sprinters coming through the system to feed into an elite squad that was thin on the ground.

“That came with a lot of belief put on to us,” says Capewell. “People coming in and saying ‘we think you can do this and we're backing you'. It's not that that's not been there in the past, but it's more prevalent now.”

Finucane, 21, adds: “She had a lot of confidence in us. She was really driven by us and I think that gave us a lot of confidence.

“We had a voice, people heard us and people saw us and then that came on to the track and people were like ‘oh these girls can do it'.” After becoming a mother in 2022, Marchant returned to find strength in depth in “a group of eight or nine girls who were performing at a really high level”.

“I was doing everything I could leading into Tokyo but I never had anyone chewing at my heels or anyone pushing me to go faster,” she says. McCulloch left the GB programme 14 months after joining, but her impact continues to be felt. With former men's coach Scott Pollock now at the helm, Capewell says “that momentum hasn't gone anywhere”.

The focus, under both McCulloch and Pollock, has been on ‘happy head, happy legs', a focus on the riders as people first and athletes second. Away from the track, Capewell is a keen photographer, while Marchant has her own baking business.

In 2023, Pendleton – a double Olympic and nine-time world champion across the sprint disciplines – was brought in to spend three days with the squad, sharing her knowledge and experience.

“We've been very proactive about how we wanted that programme to run,” says British Cycling's performance director Stephen Park.

“We recognised that some of the ways that it had run in the past were perhaps not the best. So we wanted to learn lessons from that.

“Kaarle was given support to develop those riders into young, positive, confident women that felt that they did have the right to a seat at the table.

“And that meant that they did lots of things away from the track trying to develop them and develop their confidence, as well as lots of stuff on the track.

“Our physiology team and nutrition team have been really conscious around trying to be very specific about programmes for women rather than slightly altered programmes for men, which historically they probably were.”

Potential in Paris

Since Tokyo, the squad's results have slowly turned for the better. Successive world bronzes in the team sprint came in 2021 and 2022, but 2023 was the year they really caught the eye.

At the World Championships in Glasgow, Finucane won sprint gold while she, Capewell and Lauren Bell won silver in the team sprint.

In Apeldoorn in January, Marchant – who is racing quicker then ever before – became the first British woman to be crowned European champion in the 500m time trial, meaning Great Britain currently boasts the European champions in the event in the elite, under-23 (Rhianna Parris-Smith) and junior (Georgette Rand) categories.

Looking ahead to Paris, Olympic qualification will be confirmed in April but Finucane currently tops the UCI rankings for the individual sprint, while Great Britain lead the team sprint rankings. For the first time in 12 years, Team GB heads to an Olympics among the favourites for the women's team sprint gold, with exciting medal chances across all the sprinting events.

“I am really confident they're going to do well,” says Park.

“It's actually a joy to be part of their journey, because it's great to see them enjoying their riding, feeling that they're in control of their programme, and they're writing themselves into the history books.

“Other people are trying to help create and support what they want, but ultimately those women are doing it for themselves.”

— CutC by bbc.com