“How would you like it if we started sending official delegations to Honolulu to meet with separatist leaders who want Hawaiian independence from the United States? What would you do if we started selling them weapons?”

It might seem like a false equivalence, but this is a line of argument often deployed by China's legion of armchair warriors, who take to social media to condemn any visit to Taiwan by US government officials – and especially members of the US Congress. China sees self-ruled Taiwan as a breakaway province that will eventually be under Beijing's control, and so, to these social media users, such visits are an unacceptable provocation and interference in China's internal affairs.

Of course, these visits – like the one being made by Representative Mike Gallagher, head of the US House's China committee, this week – are viewed very differently in Washington and Taipei, which sees itself as distinct from the Chinese mainland, with its own constitution and democratically-elected leaders.

But it does raise the question, what is their purpose? Are they a genuine show of support that helps deter China – or are they publicity stunts that serve to provoke Beijing, and solidify the view that Washington is intent on the permanent separation of Taiwan?

The visits are not without consequence. How the US handles its relationships with Beijing and Taipei will do much to determine whether the current tense stalemate across the Taiwan Straits remains that way, or gets a lot worse.

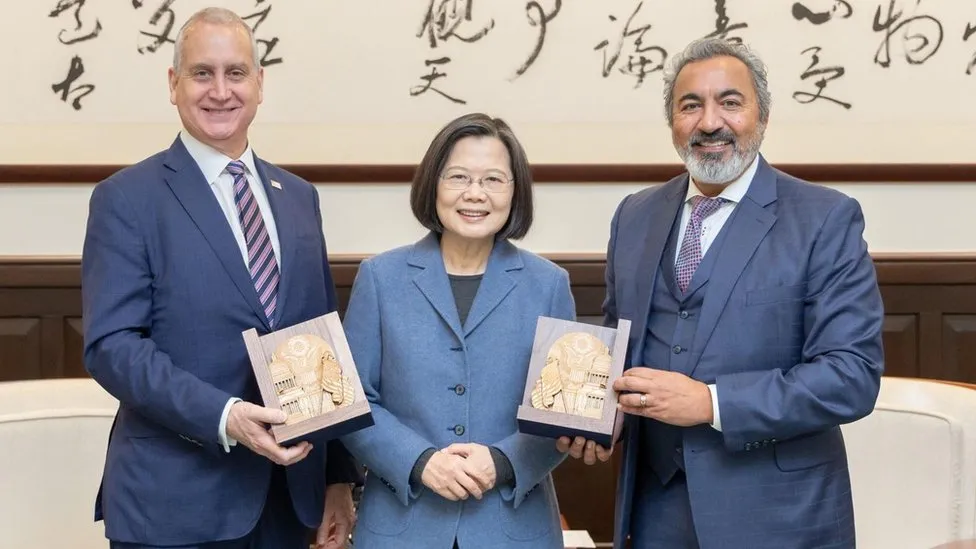

“We have come here to reaffirm US support for Taiwan and express solidarity in our shared commitment to democratic values,” said Congressman Ami Bera and Mario Díaz Balart as they wound up a trip here in January. They were the first to make the pilgrimage to Taipei following the 13 January presidential election.

Now, the hawkish Rep Gallagher – who told the Guardian last year Beijing was aiming “to render us subordinate, humiliated and irrelevant on the world stage” – arrives with a number of colleagues a month later. It is likely they will not be the last. Since 2016, the number of US congressional delegations crossing the Pacific has increased dramatically. In 2018, for example, six lawmakers made the trip. Last year, 32 visited, according to a tally by Global Taiwan.

That trend has been actively encouraged by Taiwan's current President Tsai Ing-wen, and does not appear to have been discouraged on the US side. Indeed, President Joe Biden has been the most explicit of any US leader yet in his defence of Taiwan – albeit while still continuing a commitment to America's One China policy.

“It's important,” says J Michael Cole, a former Canadian intelligence officer and one-time advisor to President Tsai. “The United States keeps saying we have a rock-solid commitment to Taiwan. But you need a public component to that exercise. That's what rattles Beijing, that's what gets journalists writing about it.”

And unlike the $80m (£63m) grant signed off by Biden in November, these visits also represent a low-cost way for the US to re-assure the people of Taiwan that they do mean what they say.

“We have research that shows high-level visits increase people's confidence in the US-Taiwan relationship,” says Chen Fang-yu, a political scientist at Soochow University in Taipei.

Such visits promote a more friendly attitude towards America from those who remain sceptical of whether the US would actually turn up if Taiwan were attacked by China, he explains. However, there are others here who have imbibed conspiracy theories, many of which originate from across the Taiwan Strait, that America is pushing Taipei down the road to war with China, just as conspiracy theorists say it did with Ukraine's war with Russia.

Meanwhile, American congressmen and women have their own, not always selfless, reasons for coming here. The pilgrimage to Taipei is increasingly a way for those on the right to burnish their anti-China credentials to voters back home – although these days, the left appears just as keen to prove their own tough stances when it comes to Beijing.

The increased frequency, and unabashed publicity, shows how much has changed between Washington and Beijing.

“Before 2016, people thought visits here should be low key,” says Chen Fang-Yu. “They wanted to avoid angering China. But now more and more people realise that no matter what they do, they will anger China.”

Taiwan's relationship with the US Congress is deep and long. When in 1979, President Jimmy Carter broke relations with Taipei, and recognised Beijing, it was the US Congress that forced him to sign the Taiwan Relations Act. That act is what underpins the relationship with Taipei to this day. It explicitly commits the US to opposing any attempt to change the status quo across the Taiwan Strait by force, and to supplying Taiwan with sufficient weaponry to defend itself against China.

In the 1970s, Taiwan was a military dictatorship. Its US allies were Republican. The cold war was still very chilly, and the islands were seen as a bulwark against Communism. Today, anti-communism may still play a small part. But far more important is solidarity with a fellow democracy. Taiwan is no longer a Republican Party cause. In the wake of things like Trump's trade wars, arguments over Covid's origins and spy balloons being spotted in the US, support for Taiwan among Americans now spreads through both parties.

Added to this, the US also has major national security and economic interests tied to Taiwan – in particular, the semiconductor trade. It all means that, unlike with Ukraine, there a no voices in Congress calling for the US to cut military support for Taiwan. If anything, it is the opposite.

But that question remains. Do the visits do more harm than good? When Nancy Pelosi came here in the summer of 2022, Beijing responded by firing ballistic missiles over the top of the island for the first time, including over the capital Taipei. Opinion polls taken after the visit showed a majority here thought the visit had damaged Taiwan's security.

But, says J Michael Cole, what do these visits really mean for US-Taiwan relations? After all, “the really substantive aspect … such as the increasingly high-level exchanges on things like intelligence, like defence, those don't make the news”.

“Those are constructive,” he continues. “And the United States is adamant that those shall not be publicised by Taiwanese government.”

— CutC by bbc.com