Far right groups have discussed toppling the German government as they seek to harness the anger of ongoing farmer protests over subsidy cuts.

A protest is due in Berlin, with warnings the agricultural movement is being infiltrated by extremists. Our team in Germany has been working with BBC Verify to build up a picture both online and on the ground.

While the far right is piggybacking off the row, a “Germany first” narrative appears to be gaining wider traction. As farmers blockade roads over planned subsidy cuts, there have been numerous reports of neo-Nazi or monarchist groups turning up at rallies.

Telegram channels reveal fervent posts about hopes of an emerging mass resistance that could help “dismantle” the government. Small, fringe far-right groups – like the Free Saxons, The Third Way and The Homeland – have a very varied number of online followers.

But Chancellor Olaf Scholz warned this weekend that extremists were using social media to “poison” democratic debate as he described any talk of uprisings as dangerous “nonsense”. A BBC team has been to five demonstrations in the past week and monitored several more.

While many farmers – and Germany's main agricultural union – are eager to distance themselves from extremism, far-right imagery continues to appear. In the eastern city of Cottbus, we saw a man being sent away from an official protest for allegedly wearing a symbol of the Reichsbürger; a disparate far right movement that rejects the modern Germany state.

A senior organiser of the Cottbus demo told the BBC they learned later that known far-right figures had remained within the hundreds-strong crowd, made up of a cross-section of people well beyond the farming community.

There are also examples of the Landvolkbewegung flag being displayed, which was an antisemitic agricultural movement that began in the 1920s.

The vast majority of banners we saw don't carry overt far-right messaging but instead centre on anger at the treatment of farmers as well as frequent calls for an end to the “traffic light” coalition government.

Unions are demanding ministers reverse plans to phase out fuel subsidies – which can be worth up to €3,000 ($3,300; £2,600) a year for an average business – while farmers speak of much longer-standing grievances about “burdensome” rules and regulations.

But strikingly often, both farmers and others who attend these demos have told us they feel too much money is being sent abroad – a common refrain of the far-right.

Supporting countries like Ukraine may be the correct thing to do says Silvio – a farmworker in the eastern state of Brandenburg: “But… we can't spend everything and nothing is left for the home country, for the farmers.”

“Prices have collapsed and Ukraine grain is undercutting our prices further,” he add. While Edelgard, a retiree who turned out to support the demo in Cottbus agrees. “There is money for people all over the world but not for our own people,” he said.

Neither Silvio or Edelgard say they support the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), this type of “Germany First” narrative is often echoed by AfD party figures.

The AfD is reaching record highs in the polls, currently placing second – and Jurgen, a metalworker, is clear in his support for the party.

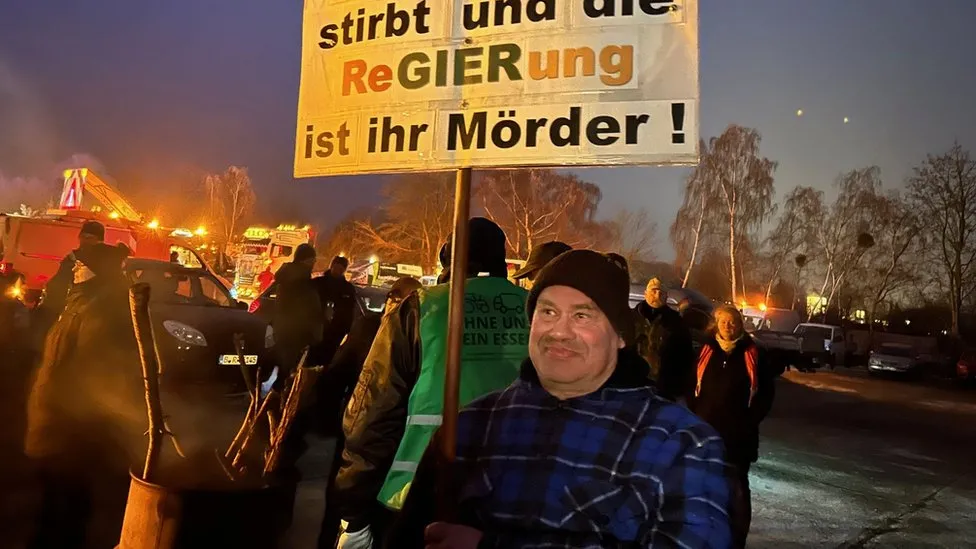

We meet him at a farmers' demo on Friday evening, on land by a petrol station on the outskirts of the town of Werneuchen, north-east of Berlin.

Music blares from a huge speakers cased in a wheelie bin as people huddle round fire pits in a crowd made up of farmers, families, tradesmen and even an off-duty police officer.

Jurgen's placard reads, “The republic is dying and the government is its killer.”

He defends the violent rhetoric and expresses a widely shared anxiety about the cost of living, claiming many at the rally would also back the AfD.

“All of them want to get rid of the government, that's for sure.”

Jurgen doesn't claim to be a revolutionary but talks about removing the coalition government at an election or “firing them” through the courts.

The AfD has been seeking to champion the farmers' cause, despite previously advocating for fewer agricultural subsidies.

It comes as a debate about whether to ban the party reignited after investigative outlet, Correctiv, reported that senior AfD figures were present at a far-right meeting at which plans to deport millions of people were discussed.

Meanwhile, the ruling coalition of Social Democrats, Greens and Free Democrats is still struggling in the polls. Chancellor Scholz has insisted his government is taking the farmers arguments seriously and that ministers have offered a “good compromise” after partially watering down their initial subsidy cut proposals.

Far-right groups have been seeking to put their own “spin” on the demonstrations, says Miro Dittrich – a senior researcher from the monitoring organisation CeMAS.

“They know their overall, usual positions aren't always popular so they have to rely on proxy issues.”

And while there's little evidence that the far-right has fully managed to hijack the ongoing farmers protests, it's also clear that broader discontent – about issues like inflation and globalization – is being absorbed into an agricultural movement that is simultaneously energising Germany's political extremes.

— CutC by bbc.com