The million dollar question in journalism, if little known outside the industry, is “cut through” – how can a story be made to not only reach an audience, but keep them hooked.

It is a challenge that investigative journalist Nick Wallis, one of the key voices to first expose the post office scandal at the turn of the millennium, will know all too well. His work helped give a voice to over 700 workers prosecuted after faulty post office software, known as Horizon, made it appear that money was missing.

The fight for justice in the decades since has seen Wallis publish his own book on the scandal (serialised in the Daily Mail), alongside investigations by BBC Panorama, Computer Weekly and Private Eye amongst others.

But 25 years on from the first convictions for theft and fraud, it is the four-part ITV drama Mr Bates vs The Post Office that has renewed mass public interest in the scandal like never before.

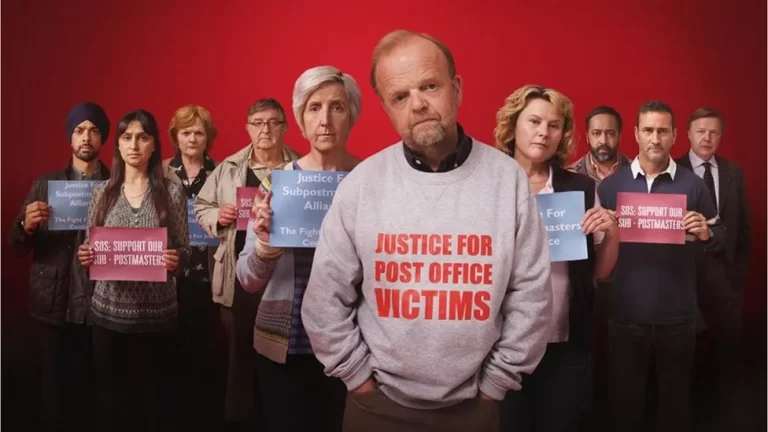

Watched by nine million viewers so far according to ITV figures, the mini-series centres on the story of sub-postmaster Alan Bates, played by actor Toby Jones, who led and won a legal battle paving the way for dozens of convictions to be overturned.

Since the series began airing on 1 January, 50 new potential victims have contacted lawyers, some of whom were former sub-postmasters prosecuted by the Post Office. Westminster has tried to keep pace, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak calling the case an “appalling miscarriage of justice” in an interview with the BBC's Laura Kuenssberg on Sunday.

The government is now under pressure to overturn wrongful convictions and deal with compensation, with ex-Post Office boss Paula Vennells agreeing to hand back her CBE in response to the public outcry. It marks a long-awaited breakthrough for victims. But why now, and why in response to a TV show?

Emotional impact

For the show's executive producer Patrick Spence, it proves the unique power drama can hold in forging human connection. He told BBC Radio 4: “Drama can go inside the homes of the sub-postmasters who so suffered and dramatise the pain that they went through.

“[It] can do something that a documentary and a newspaper article can't… they can bring to life the true emotional impact on the people who were victimised by the Post Office's abhorrent behaviour.” But these two mediums, rather than working in competition, often complement each other to forge a lasting impact, says arts writer Fiona Sturges.

“I think it's easy to look at the media as a separate entity when so often these types of dramas are inspired by stories painstakingly researched over years by journalists.

“But I also think TV dramas can bring a level of humanity and colour that print media can't always manage, largely due to limits on space and reach.”

The response is far from the first time a docudrama has caught public attention and put politicians under pressure to act. Cathy Come Home, Ken Loach's BBC television play about homelessness, sparked a huge public reaction when first broadcast in 1966.

As Mark Lawson wrote in the Guardian, the charities Crisis and Shelter “doubtless benefitted” from the parliamentary debate and raised awareness of disadvantage that followed the drama. Sturges adds that it allowed audiences to “really dwell on what that would be like and to create a space where statistics become people with complex characters and stories”.

In a similar vein, she says Jimmy McGovern's Hillsborough, which dramatised the fight for justice by the families of 97 Liverpool fans killed during the Sheffield Wednesday stadium crush in 1989, took the uneasiness and ugliness gleaned from extensive journalism on the topic and turned it into an “emotionally-charged human story”.

Centred around the two years after the tragedy when the original inquest recorded a verdict of accidental death in 1991, its airing five years later helped solidify a shift in public opinion. When the verdicts were eventually overturned in 2016 and the deaths ruled unlawful, then-Walton MP Steve Rotheram called the docudrama “massively influential” in pushing for the truth.

Fighting the system

McGovern told the BBC he was approached to make the drama by the Hillsborough families not because the story wasn't known, but because it was framed in a certain way – and a docudrama turned the narrative around.

It made it a story about institutional failure after fans had wrongfully been blamed for the disaster. It made the families the heroes and rightful victims of the story. This same sense of indignation has been present in the reaction to Mr Bates, says Spence, who sees the response in political terms.

“As a country we feel unheard by our politicians and by our government. And I think what this drama seems to have done is tapped into that rage.

“Our ambition was simply to allow them to feel that their story was heard… but what people have connected with I think is a sense that nobody is listening to the people that deserve it the most.”

The frenzied political and state response, then, including potentially passing a specific law to exonerate those affected, can be seen as an act of preservation.

“There is a growing feeling that the public mood, prompted by the drama, leaves those in government with no alternative but to act, be seen to act, and to do so quickly”, wrote BBC political editor Chris Mason on Tuesday.

Toby Jones, the actor portraying Mr Bates, believes the response shows the enduring value of drama in progressing public awareness and national debates.

“Drama is constantly downgraded as a subject of importance, but it's historically always been a place that people, even if they don't believe that it can deliver change, nevertheless it suggests change… and so it cannot be ignored.

“In most of the political upheavals in history, not least ancient Greece and revolutionary Russia, that drama has been at the centre of political change, that people have used it to humanise, dramatise and bring forth change.”

— CutC by bbc.com