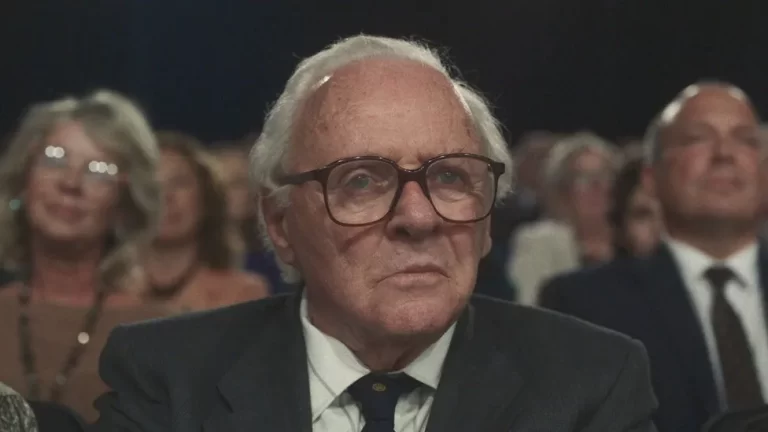

A British stockbroker who helped save 669 children from the Nazis in World War Two didn't think of himself as a hero. Actor Sir Anthony Hopkins, who plays him in a new film, disagrees – as do those he helped.

Sir Anthony Hopkins joins our Zoom interview drinking a cup of English breakfast tea. He's at his home in Los Angeles and, for him, it's the morning. The double Oscar winner regularly posts to his 4.8 million Instagram followers from this house.

“Americans can't make tea,” he confides. I tend to agree. The 85-year-old screen legend has joined to discuss his new film, One Life, and his role as Sir Nicholas Winton.

Sir Anthony (or Tony, as he says I must call him) doesn't want to “take credit” for the movie because Winton is “the hero of the piece”. Sir Nicholas was behind the Kindertransport trains that brought mainly Jewish children out of the former Czechoslovakia before the start of World War Two.

“He didn't want to be regarded as a hero. He just hoped that we would learn from it.” When Sir Nicholas was interviewed in 2014, a year before his death aged 106, he told the BBC: “There was nothing heroic about it. It was just a question of organisation and work.”

But what he – and others – did to save the children was heroic. He didn't talk about his actions for nearly 50 years, until his story appeared in the Sunday Mirror and on the BBC's That's Life.

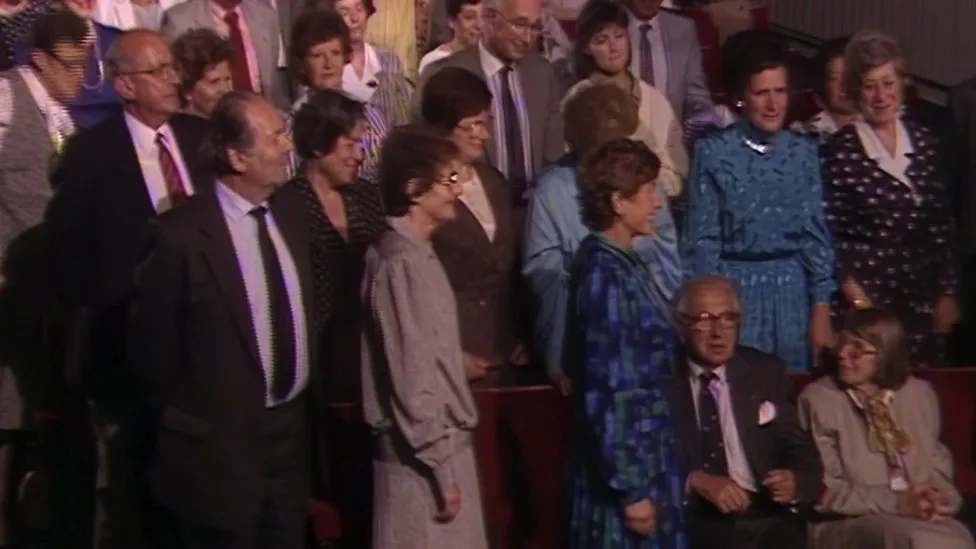

Unbeknown to Winton, Dame Esther Rantzen's programme had gathered survivors who had been saved by him.

“Can I ask,” said the presenter, “is there anyone in our audience tonight who owes their life to Nicholas Winton? If so, could you stand up please?”

Everyone on the front five rows did. It was an incredible moment of TV. Johnny Flynn, who plays the young Winton in the film, tells me Sir Nicholas dwelled for decades on what he hadn't managed to do, rather than what he had.

“The last train with 250 kids was due to leave the day that Germany invaded Poland and all the borders shut. So for him it is a tragedy, and he almost can't admit to himself what he knows to be true, which is what happened to those children.”

Only two of them are believed to have survived the war. Sir Nicholas, says Flynn, felt “deep shame” about it. Yet about 6,000 people are thought to be alive today because of what he, and other volunteers in Prague, pulled off – against the odds.

Some descendants of the Kindertransport children were in the audience when the One Life film recreated the memorable That's Life scene.

“It was really quite an emotional moment,” Sir Anthony tells me. “But I think this whole story has affected me and has actually stayed with me throughout the whole of my life.” The Welsh actor was born in 1937 and was 18 months old when war was declared. He remembers “the bombing of Swansea and the air raids”.

He also recalls going to London with his parents in 1945 when “the whole of Europe was in rubble”. His father went to an exhibition of the shocking first photographs to emerge from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after it was liberated by British troops in April 1945.

The young Tony and his mother “sat on a park bench”, having been told “you can't bring the boy in here”. Afterwards, his father “said something which has stayed with me all my life. He said, ‘They're walking skeletons'. The tragic thing is that we don't seem to learn”.

Sir Anthony adds that he agrees with Sir Nicholas' view on averting conflict, which was that “the only way through is compromise”.

‘Appalling'

“Give thought and heed to the other person's point of view,” Sir Anthony continues. “Instead of the culture we now live in: ‘No, you're wrong, I'm right'. It's appalling.” Flynn thinks One Life is “a good story to tell now”, with “two huge conflicts” bordering Europe and causing violence and turmoil.

“I know films don't change the world, but they can make people think for a bit. I think it is up to people to stand up for what they believe is right and hopefully this story can awaken that.” I also have the privilege of meeting Renate Collins, who, aged five and then called Renate Kress, was on the last Kindertransport to make it out of Prague.

She had chickenpox and a temperature of 104 that day. Her mother wanted to delay her precious daughter's departure.

“Our doctor said, ‘If you don't put her on this train, she'll never go'. And he was quite right, because the next train didn't.” Renate was very happily fostered and later adopted by a family in Rhondda.

She'd written to them before her arrival, telling them she didn't like spinach and could be a very “good girl” if she was given plenty of ice cream. But “there wasn't much ice cream during the war”, she tells me.

Renate continued to receive letters from her parents, including, heartbreakingly, the last letter in 1942, facilitated by the Red Cross from the Theresienstadt concentration camp, north of Prague. In just 22 words (the maximum allowed was 25), they wished her: “Many birthday wishes. We think continually of you. Are well, hope you too. Much love, kind regards and thanks to your fosterparents.”

Sixty-four of Renate's family members, including her parents, were murdered by the Nazis. She has donated all their correspondence to the Wiener Holocaust Library in London, which holds the UK's largest Holocaust archive.

Renate was in the second row for the That's Life recording in 1988, which she says was a “very emotional experience”.

“We were sort of excited beforehand, but we were quite quiet afterwards, because we suddenly met the gentleman who brought us out.” Like many survivors, Renate later got to know Sir Nicholas.

“He was very introverted,” she says. “He didn't want anybody to know, actually. He didn't want any accolade.” As one of Britain's most revered actors, Sir Anthony has received many accolades, not least Oscars for The Silence of the Lambs in 1992 and The Father in 2021.

But he's modest as he approaches the grand age of 86.

“I've been the most fortunate person in the world,” he tells me. He's “facing the inevitable – and I feel more at peace with that than I've ever done”.

‘Compassion and understanding'

“I don't even know why I act, so when any young actor says, ‘How do you do it?', I say, ‘I don't know. Learn your lines, show up and don't bump into the furniture',” he laughs. “But use compassion, compassion, compassion – and understanding.”

Sir Anthony is sitting in front of a bookcase that includes works on various great artists, Rosetti and Hockney among them. He's an artist himself and tells me he had a show in Las Vegas recently. He's also a pianist and composer, and often posts it all on his huge social media profile.

So who is the real Anthony Hopkins? He chuckles.

“I'm surprised I'm still here. I've been a sinner all my life, I've been a bad boy. But I'm just grateful to get up in the morning. I paint, I play the piano, I write and compose music.

“I have to, because we're a long time dead. And I relish every moment I've got now.”

And with that, he heads off, English breakfast tea still in hand.

— CutC by bbc.com