When New Zealand's new government announced it was scrapping the country's world-leading tobacco laws, it came as a particularly hard blow to Māori people.

With the Indigenous community having the highest smoking rates, its leaders had fought for reforms for years. The country's model was the first to spell a complete end to smoking – and so was hailed by health advocates globally.

From 2024, the laws would have cut nicotine levels in cigarettes to non-addictive levels, eliminated 90% of retailers allowed to sell tobacco, and created “smoke-free” generations of citizens by banning cigarette sales to anyone born after 2008. But with the measures now abandoned, Māori stand to lose the most, advocates say.

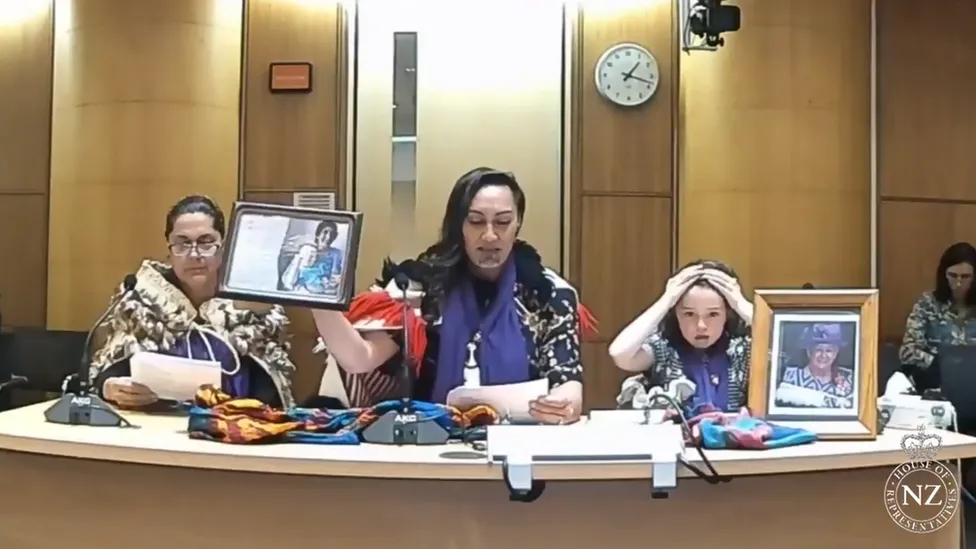

Last year, Teresa Butler and her six-year-old daughter sat in front of a room full of politicians, begging them to enact the laws. Dressed in a traditional feathered cloak, her voice quavered as she thrust a photo of her mother at the committee. She presented the death certificate.

Cause of death: Emphysema, the result of more than 30 years of tobacco smoking. Teresa had her first cigarette aged eight. She recalls running down to the shops in Christchurch, with five dollars in hand and a note from her mum for a packet of smokes.

She only kicked the habit when she fell pregnant.

“I wanted a healthy baby to continue a healthy strong whakapapa [family line],” she said. She has spent the last seven years of her life as an anti-smoking counsellor, going into Māori neighbourhoods to try and wean people off the deadly addiction.

These days, only 8% of New Zealand's adult population are daily smokers, but the number is more than double that- 19.9% – among Māori. It is even higher among Māori women.

It takes a toll, not only on health but finances. A packet of cigarettes in New Zealand costs NZ$40 (£19; $24) on average. Chain smokers can inhale a pack a day.

“It's stress, it's a lack of education, they have children, they're single mums,” says Ms Butler, relaying a typical encounter.

“I go into a home and I can clearly see her kids don't have any nappies on. There's no food in the cupboard. And I'm saying to her: ‘It's winter time, you've got no power. Why don't you have any money?' And she'll tell me: “Because I've just spent the last $30 on smokes.”

Smokers tell her they want to kick the habit but feel trapped.

“They say to me: ‘Look, it's too easy to access this Teresa. I can wake up at one o'clock in the morning, have anxiety, be depressed and go down to the local shop, the 24-hour petrol station and purchase cigarettes.' It's just a quick fix, just like alcohol.”

Targeting tobacco, not people

The proposed policies – especially denicotisation and the so-called Smokefree generation – have never been implemented anywhere. But public health researchers considered New Zealand – a high-income country of just over five million people – an ideal setting to try and achieve tobacco “endgame”.

What was new here was the focus: targeting the industry, not the individual. Almost all smokers will tell you that they want to stop, researchers say. The problem, for many, is individual capability and access to resources.

Like other countries, New Zealand had already had anti-smoking measures in place for years: excise increases on cigarettes, a Quitline phone service, and mass media campaigns carrying health warnings.

But while these helped drive down the smoking rate for European and Asian populations, the rate among Māori and Pasifika groups remained stubbornly high at around 20%.

“The problem we realised was because it was reliant on individuals too much,” says Andrew Waa, an associate professor of public health at the University of Otago who is Māori and who has led several tobacco control studies in the country.

He says these measures targeted “more superficial aspects” of tobacco control – for example focusing on helping people quit – instead of targeting fundamental causes for why people take up smoking and continue to smoke – like the widespread availability of cigarettes, and the tobacco industry's role.

And the resources needed to quit aren't equally distributed across New Zealand, researchers say. There remain significant hurdles. There are many drivers behind “health inequity” – but the underlying reasons are rooted in New Zealand's colonial history. White Europeans took over the Pacific nation in the 18th century.

“Colonisation is an underlying driver of ethnic inequalities in smoking behaviour,” Associate Prof Waa and other researchers wrote in the Tobacco Control journal last year. They noted Indigenous' people's experience of generational theft, racism and cyclical poverty were the “basic causes” affecting access to income and housing and overall health.

So when the Smokefree measures were introduced in 2021, the resounding praise from public health circles was rooted in the view that such policies would vastly improve health equity.

And in a clear example of best practice, where policy is enacted not “on” Māori but “by” Māori, the laws were also the direct extension of a political push by Maori politicians in the mid-2000s, when one MP first suggested an end to tobacco sales.

In 2010, Māori legislators set up the country's first large-scale inquiry into tobacco's harm on Māori and other communities nationally- the parliament inquiry heard from a range of groups across the country. The results led to the New Zealand government in 2011 setting one of the most daring public health targets in the world: a Smokefree country by 2025, with smoking prevalence under 5%.

However the National government at the time did little by way of policy to achieve it, researchers say. It was only Jacinda Ardern's government, a decade later, who decided to launch a package of radical reforms to get the country and in particular its Māori people across the finish line.

She appointed Ayesha Verrall, a doctor and epidemiologist, as health minister – who prioritised Māori community consultation in shaping legislation. The government further dedicated $14m to community health programmes, and set up Te Aka Whai Ora, the Maori Health Authority, an independent government body that sets Māori health policy and tailors the country's health system delivery to Indigenous people.

The scientific modelling backed up the Smokefree reforms. Simulation studies conducted by Associate Prof Waa and other researchers concluded the measures would see the smoking rate for Māori drop to 7.8% by 2025, compared to a 2040 timeframe under previous smoking policy.

More profoundly, the mortality gap for Māori women would be shortened 23%, for Māori men nearly 10%.

“It is unlikely that any other feasible health intervention would reduce ethnic inequalities in mortality by as much,” the researchers wrote. But New Zealanders in October voted in a change of government.

The conservative coalition then said it intended to repeal the health laws to fund tax cuts – a policy blindside given the leading National party never once mentioned the Smokefree laws during campaigning. The new government also plans to dismantle the Māori Health Authority.

“We thought that once the legislation was passed last year it was a done deal. So we're really confused as to how and why this can happen,” says a furious Ms Butler.

“It's heartbreaking because this is life changing, life-saving legislation, particularly for Māori,” she says. Currently about 5,000 people die each year in New Zealand from smoking and smoking-related problems – nearly a 1,000 of whom are Māori.

National has said they feared the smoking crackdown would fuel an already existing black market for tobacco in New Zealand and increase crime – arguments first used by tobacco companies opposing the laws.

Prime Minister Christopher Luxon argued that reducing the number of retailers would turn the shops left selling tobacco into a “massive magnet for crime”. Meanwhile, Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters has argued the smoking ban is a violation of people's rights and free choice.

The finance minister also revealed that the “about a billion dollars” in tax raised from cigarette sales would go directly into funding “tax relief for working Kiwis”. It has blamed negotiations with Act and New Zealand First, two right-wing, populist minor parties it needed to form government, for forcing their hand.

The New Zealand Health Minister's office admitted to the BBC the repeal of Smokefree laws were “not a National Party policy – but that's the nature of a negotiation.” But previous government modelling had shown that Smokefree would save the country's healthcare system NZ$2.29bn (£1.12bn;$1.4bn) over two decades.

Dr Shane Reti, the new Health Minister, has faced calls from the nation's practitioners to step down from his medical registrations – given his abandonment of the public health policy. His office told the BBC the government “remained committed to reducing smoking rates” but did not answer questions on how it would achieve that now with the Smokefree policies scrapped.

Critics have also raised questions about the tobacco industry's influence in the policy reversal. New Zealand had been viewed as the dangerous ‘endgame' precedent for Big Tobacco, Prof Waa says. Since New Zealand announced the laws in 2021, they had inspired other countries; the UK this year also announced ambitions for a smokefree generation.

The National party declined to answer the BBC's questions about political funding from tobacco companies. Meanwhile, health activists and Māori leaders are fighting again to keep their hard-won reform. More than 20,000 New Zealanders signed a petition last week calling for the laws to stay.

“We simply cannot afford to go backwards, while our whānau continue to die at the hands of this product,” read the Hāpai Te Hauora petition.

Thousands also protested on the streets in capital city protests around the country last week, criticising the incoming government for its “anti-Māori” policies with many singling out the dismantling of Smokefree laws.

But there are murmurings and concerns that the government, with a majority in parliament, could scrap the laws early next year.

— CutC by bbc.com