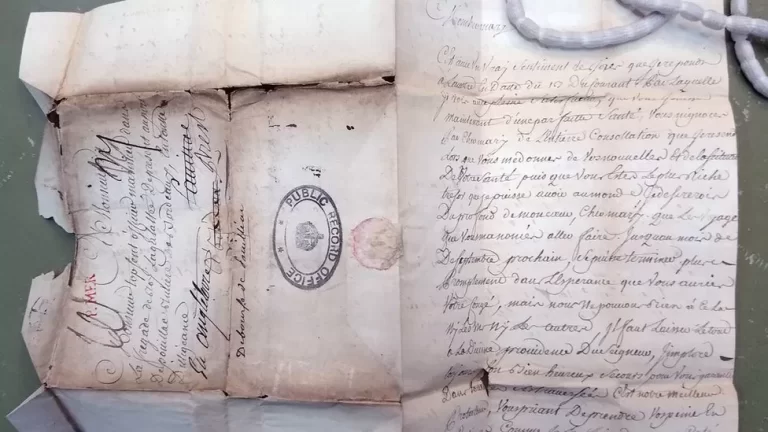

Letters confiscated by Britain's Royal Navy before they reached French sailors during the Seven Years' War have been opened for the first time.

Written in 1757-8, they were sent by loved ones for crew onboard a French warship, but never reached them. Prof Renaud Morieux, who discovered the letters, said they were about “universal human experiences”.

The Seven Years' War was a battle mainly between Britain and France about control of North America and India. It ended with the Treaty of Paris, which gave the UK considerable gains.

Prof Morieux, a University of Cambridge academic, unearthed the collection of 104 letters from the National Archives in Kew, and said it was “agonising how close they got” to reaching their intended recipients onboard the Galatee.

The French postal administration took them to multiple ports in France to attempt delivery, but were unsuccessful.

The Galatee was captured by the British on its way from Bordeaux to Quebec in 1758. Upon learning the ship was in British hands, French authorities forwarded the letters to England, where they were handed to the navy and ended up in storage.

British Admiralty officials deemed the letters had no military significance. Prof Morieux said he only asked to look at the box in the archives “out of curiosity” before discovering them.

“I realised I was the first person to read these very personal messages since they were written,” he said.

“Their intended recipients didn't get that chance. It was very emotional,” said Prof Morieux, whose findings were published in the journal “Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales”.

Prof Morieux identified every member of the Galatee's 181-strong crew, with letters addressed to a quarter of them – he also carried out genealogical research into the men and their correspondents. They include a letter from Marie Dubosc to her husband, the ship's first lieutenant, Louis Chambrelan. She wrote: “I could spend the night writing to you… I am your forever faithful wife.

“Good night, my dear friend. It is midnight. I think it is time for me to rest.”

Researchers say she did not know where her husband was or that his ship had been captured by the British. He did not receive her letter and they did not meet again, with Dubosc dying the next year in northern France.

Chambrelan returned to France and remarried in 1761. In another letter, Anne Le Cerf told her husband Jean Topsent, a non-commissioned officer: “I cannot wait to possess you.”

“These letters are about universal human experiences, they're not unique to France or the 18th century,” Prof Morieux said.

“They reveal how we all cope with major life challenges.”

“When we are separated from loved ones by events beyond our control, like the pandemic or wars, we have to work out how to stay in touch, how to reassure, care for people and keep the passion alive.

“Today we have Zoom and WhatsApp. In the 18th century, people only had letters but what they wrote about feels very familiar.”

— CutC by bbc.com