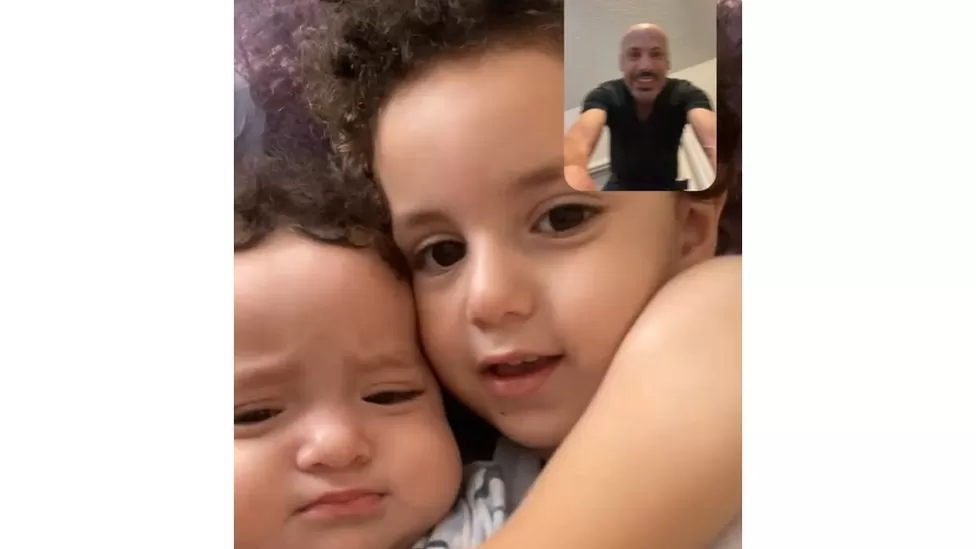

Almost a month since the war broke out, Folla Saqer and her two children are still trapped in Gaza.

Her husband, Ramiz Younis, waits with bated breath for news that they have finally gotten out.

The children – Zain, two, and Zaina, nine months – are American citizens. Along with Ms Saqer, a permanent legal resident, they are among roughly 1,000 people who want to cross into neighbouring Egypt and begin their return to the US.

On Wednesday, more than 400 foreign passport holders and injured Gazans were allowed through the Rafah crossing for the first time since the war began. The US state department has said that includes “a number of American citizens”, though it declined to provide specifics, only adding that exits will “continue over the next several days”.

But a lack of clear information – as well as what critics say is a haphazard and often vague correspondence from government officials – is stoking growing frustration among some Palestinian Americans as they, or their families, scramble to get out of Gaza.

Mr Younis says his heart sinks with each new message or phone call from Gaza. He always expects to hear that something bad has happened because, in his own words, “no good news is coming out of the area”.

So desperate is the 51-year-old to have his wife and children back home that, on Monday, he filed a federal lawsuit accusing the US government of discrimination and failure to do its duty towards its citizens. The legal action, which names Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin as defendants, alleges the family has been “let down and ignored as if we are second class citizens”.

“Bringing out citizens to safety is supposed to be a top priority for them in a time of war like this. Why are they not doing it?” he asked. The Gaza-born Mr Younis returned to the enclave four years ago after marrying Ms Saqer. The couple resettled in Baltimore, Maryland, last year.

But Ms Saqer, feeling homesick, took the children to Gaza on a short trip earlier this year. She intended to come back in mid-October, by which time Mr Younis had completed their move to Little Rock, Arkansas.

When the conflict erupted, Mr Younis immediately counselled her to travel towards the Egyptian border and wait for an opportunity to cross. In those first three days, he said, “I didn't even want to get in touch with the state department. The crossing was open and I thought I can do this on my own.”

Ms Saqer took the children to her sister's place in Rafah, a 10-minute drive from the border. But the first time she attempted to leave, the waiting area by the crossing was bombed. In the frantic rush for cover, she left all their luggage behind.

With the crossing closed, Mr Younis provided his family's information to the state department. He received an email on 14 October with instructions that the crossing would open for five hours the next day. At great personal risk, Ms Saqer and the children again went and waited. But they were not let through.

Similar updates, including from local US embassies, would follow in the ensuing days, urging Ms Saqer to go to the border. She made four more trips. None were successful.

“Whenever we have the chance to communicate, my wife asks me for news [from the government],” said Mr Younis.

“Sometimes I don't have news, but I keep the hope alive. I need to keep the hope alive even if there is nothing happening.”

In a statement to the BBC, a state department spokesperson said it has “been communicating 24/7 with US citizens and providing them assistance. We have sent messages to every US citizen who contacted us to inform them of options for departure assistance”.

But, according to Mr Younis, communications from the government have been scarce and scattershot. The latest correspondence, on Tuesday, offered “reliable information” that “limited” departures from Gaza may begin this week.

The next day, Ms Saqer saw a list of foreign passport holders with permission from the Palestinian Customs Authority to cross into Egypt; her name was not on it and, while US officials have promised a new list daily, it remains unclear how many people will be on it and when she will be able to leave.

Justin Eisele, an attorney representing Mr Younis, said his client's lawsuit draws attention to an apparent lack of urgency.

“They're not being given equal protection under the law. The United States has treated Palestinian Americans in Gaza right now 100% differently than anyone else in the previous history of our country,” he said.

The Okals, a suburban Massachusetts family, are also trapped in Gaza. Abood Okal and Wafaa Abouyzada took their one-year-old son, Yousef, to the enclave last month to visit the grandparents he had never met.

The family shared meals, went to the beach and rode horses together – until Hamas launched its attack on Israel six days before the Okals' intended departure.

From Ms Abouyzada's home in Jabalia, in northern Gaza, the trio heeded Israeli warnings and fled south. Nobody knows if their home – which is located very close to a refugee camp bombed on Tuesday – is still standing.

For nearly three weeks, the trio have waited in a single-family home in Rafah with 40 other people, holding out hope they can eventually cross into Egypt. Every single day, they have contacted the state department, as well as US embassies in Cairo and Jerusalem, according to Sammy Nabulsi, a family friend.

On four separate occasions, they were advised to go to the Rafah crossing. But after waiting anywhere between six and eight hours each time, they have gone home empty-handed.

“Their circumstances right now are completely dire and dangerous,” said Mr Nabulsi. The 40-person house has lost running water and fuel, he told the BBC. Its residents are limiting the number of times they flush the toilets and are pumping saltwater from the well to stay hydrated.

With no cooking oil on hand, the family is largely living off canned tuna and fava beans. Their last visit to the bakery lasted six hours and their last water run yielded only one gallon's worth for the whole house to share.

Worst of all, Yousef often wakes up screaming inconsolably from night terrors and cannot go back to sleep.

“That poor kid is just completely traumatised,” said Mr Nabulsi, adding that Yousef's parents have run out of milk for him to drink.

Mr Okal, who holds a PhD in cancer research, is a director at the Bristol Myers Squibb pharmaceutical company. Ms Abouyzada worked at a local non-profit before stepping away to care for their son. Now the family's home in quiet Medway sits empty.

“They're just the kindest people. They're really funny and sweet,” Mr Nabulsi said.

“They should be in Massachusetts. I can't for the life of me understand why we haven't gotten them out.” A real estate lawyer by trade, Mr Nabulsi says he has contacted White House and state department officials, as well as several members of the US Congress, on the Okals' behalf.

He says officials have offered shifting explanations for why his friends are unable to get out.

“They feel completely hopeless and abandoned by the US government,” Mr Nabulsi said.

“My biggest fear is the airstrikes have continued in Rafah,” he added.

“We're barrelling towards a scenario where an American-made weapon, paid for by American tax dollars, might potentially be used to harm or even kill American citizens.

“I can't live with that.”

— CutC by bbc.com