Dusty samples from the “most dangerous known rock in the Solar System” have been brought to Earth.

The American space agency Nasa landed the materials in a capsule that came down in the West Desert of Utah state. The samples had been scooped up from the surface of asteroid Bennu in 2020 by the Osiris-Rex spacecraft.

Nasa wants to learn more about the mountainous object, not least because it has an outside chance of hitting our planet in the next 300 years.

But more than this, the samples are likely to provide fresh insights into the formation of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago and possibly even how life got started on our world. There was jubilation when the Osiris-Rex team caught sight of their capsule on long-range cameras. Touchdown on desert land belonging to the Department of Defense was confirmed at 08:52 local time (14:52 GMT), three minutes ahead of schedule.

The car-tyre-sized container had come screaming into the atmosphere over the western US at more than 12km/s (27,000mph). A heatshield and parachutes slowed its descent and dropped it gently, perfectly on to restricted ground.

“This little capsule understood the assignment,” said Tim Priser, the chief engineer at aerospace manufacturer Lockheed Martin. “It touched down like a feather.” Asked how the operation went to retrieve the capsule from the desert, some of the recovery workers returning in their helicopters told BBC News' science team that it was “awesome”.

“I cried like a baby in that helicopter when I heard that the parachute had opened and we were coming in for a soft landing,” said Osiris-Rex principal investigator Dante Lauretta.

“It was just an overwhelming moment for me. It's an astounding accomplishment.” Scientists are eager to get their hands on the precious cargo which pre-landing estimates put at some 250 grams (9oz). That might not sound like very much – the weight of an adult hamster, as one scientist described it – but for the types of tests Nasa teams want to do, it is more than ample.

“We can analyse at a very high resolution very small particles,” said Eileen Stansbery, the chief scientist at Nasa's Johnson Space Center in Texas.

“We know how to slice and dice a 10 micron-sized particle into a dozen slices and to then map grain by grain at nano scales. So, 250 grams is huge.”

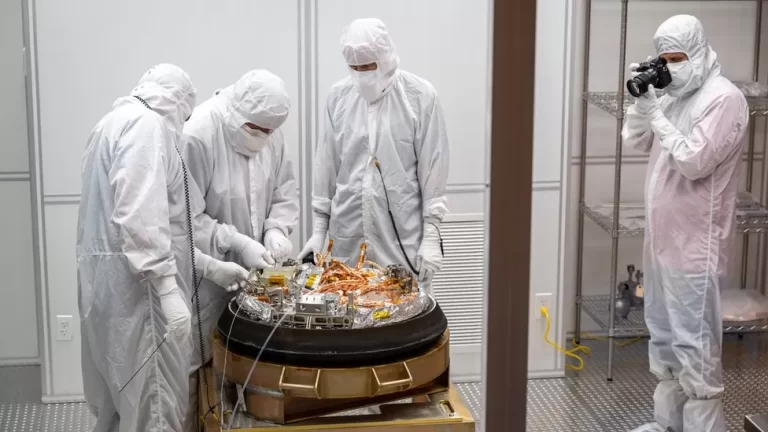

Cleanliness was the watchword out in the desert. When the recovery teams caught up with the capsule on the ground, their motivation was to bring it back to a temporary clean room at the nearby Dugway army base as quickly as possible.

If, as researchers think, the sample contains carbon compounds that may have been involved in the creation of life then mixing the rocky material with present-day Earth chemistry has to be avoided.

“The cleanliness and preventing contamination of the spacecraft has been a really stringent requirement on the mission,” said Mike Morrow, the Osiris-Rex deputy project manager.

“The best way that we can protect the sample is just to get it from the field into the clean lab that we've set up here in a hangar as quickly as possible and get it under a pure nitrogen gas purge. And then it's safe.”

This was achieved just before 13:00 local time, a mere four hours after touchdown. The lab team disassembled the capsule, removing its heatshield and back cover but leaving the sample secure inside an inner canister.

This is being flown on Monday to a dedicated facility at Johnson where the analysis of the samples will begin. UK scientist Ashley King will be part of a six-person “Quick Look” team that will conduct the initial assessment.

“I'm expecting to see a rocky type material that's very soft, very fragile,” the Natural History Museum expert said.

“It'll have clay minerals – silicate minerals that have water locked up in their structure. Lots of carbon, so I think we'll probably see carbonate minerals, and maybe some things we call chondrules and also calcium-aluminium inclusions, which were the very first solid materials to form in our Solar System.”

Nasa is planning a press conference on 11 October to give its first take on what has been returned. Small specimens are to be distributed to associated research teams across the globe. They hope to report back on a broad range of studies within two years.

“One of the most important parts of a sample-return mission is we take 75% of that sample and we're going to lock it away for future generations, for people who haven't even been born yet to work in laboratories that don't exist today, using instrumentation we haven't even thought of yet,” Nasa's director of planetary science, Lori Glaze, told BBC News.

— CutC by bbc.com